Are Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) a public alternative to the Token Economy or a defensive reaction?

- Introduction

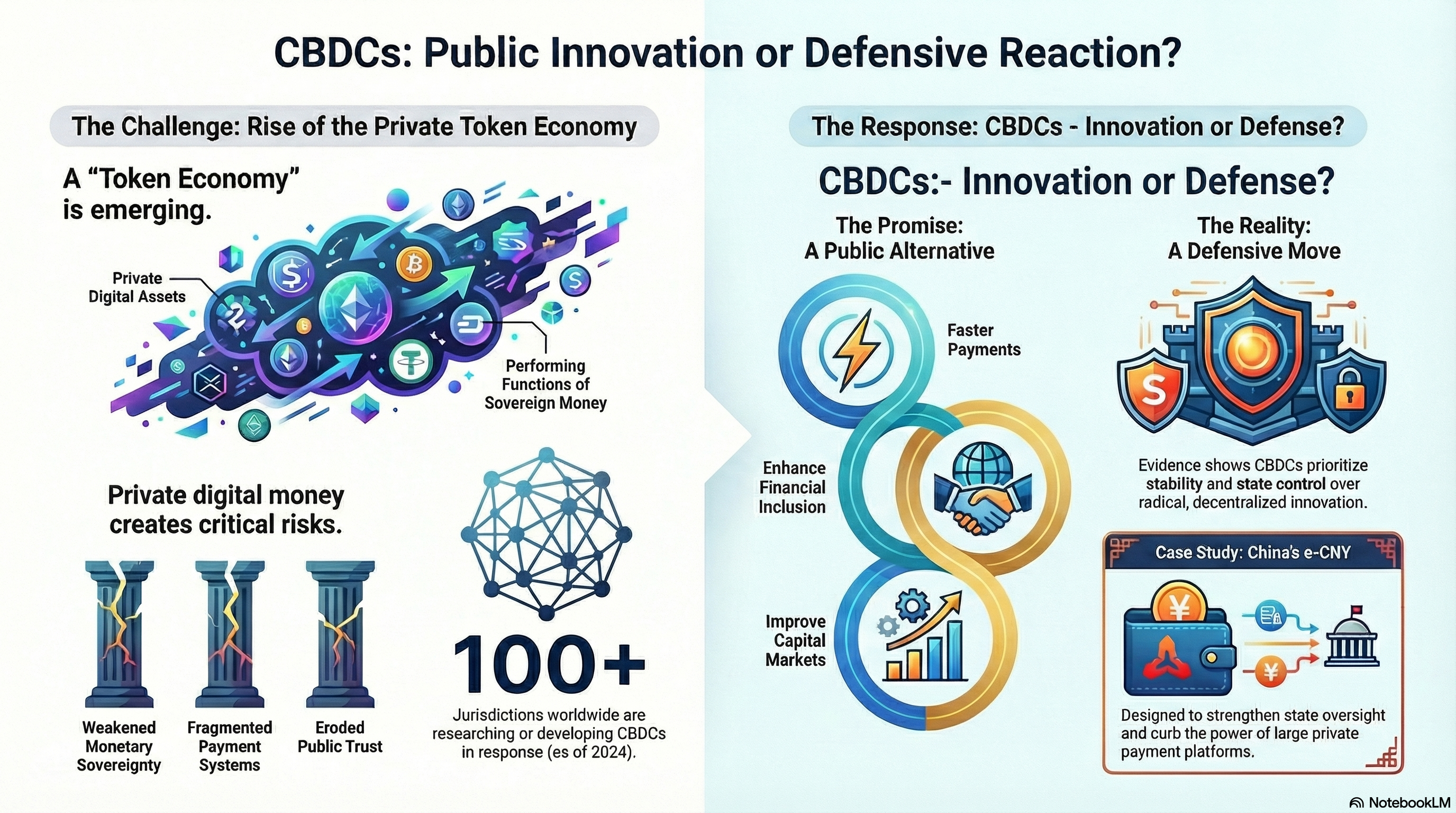

The global monetary and payments landscape is undergoing a structural transformation. Cash usage is steadily declining, digital payments are becoming the dominant medium of exchange, and private digital assets such as cryptocurrencies, stablecoins, and tokenized financial instruments have expanded rapidly over the past decade (Bank for International Settlements [BIS], 2020). These developments have given rise to what is commonly referred to as the token economy, where privately issued digital tokens increasingly perform functions traditionally associated with sovereign money.

While the token economy promises efficiency, programmability, and innovation, it also raises critical concerns for central banks. Private digital money can weaken monetary sovereignty, fragment payment systems, and erode the role of public money as the anchor of trust in the financial system (International Monetary Fund [IMF], 2023). In response, central banks worldwide have accelerated the exploration and development of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs). As of 2024, more than one hundred jurisdictions are researching, piloting, or preparing some form of CBDC (Atlantic Council, 2024).

This paper addresses the following research question: Are CBDCs primarily a public alternative to the token economy, or do they represent a defensive reaction by central banks to the rise of private digital currencies and payment platforms? The paper focuses on the policy motivations, institutional design, and early evidence from CBDC initiatives to assess whether these projects signal an embrace of token-based finance or a strategic effort to preserve the relevance of public money.

Podcast:

2. Literature Review

The academic and policy-oriented literature on Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) has expanded rapidly in recent years, reflecting growing concern among policymakers about the implications of digitalization for money, payments, and financial stability. Early foundational work by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS, 2020) defines CBDCs as digital forms of central bank money intended to complement physical cash and existing electronic payment instruments. This literature emphasizes trust, settlement finality, and legal tender status as the core attributes distinguishing CBDCs from cryptocurrencies and privately issued stablecoins.

A substantial portion of the literature focuses on CBDCs as a response to declining cash usage and the growing dominance of private payment platforms. BIS reports and central bank publications argue that, as cash becomes less widely used, citizens may lose direct access to risk-free public money, potentially weakening confidence in the monetary system (BIS, 2020). From this perspective, CBDCs are framed as a necessary modernization of public money rather than a disruptive innovation.

The International Monetary Fund has contributed extensively to the policy debate by analyzing CBDCs through the lenses of monetary policy, financial stability, and institutional capacity (IMF, 2023). The IMF’s capacity development framework stresses that CBDC initiatives require legal clarity, cyber resilience, sound governance, and coordination with the banking sector. Importantly, IMF work highlights that CBDCs should be evaluated not on technological novelty, but on their ability to advance clearly defined public policy objectives.

Another strand of the literature examines CBDCs in relation to the private token economy. Research on Asian e-money systems demonstrates that private digital payment platforms can achieve rapid adoption when they provide convenience, low costs, and strong network effects (Sun & Rizaldy, 2023). These findings raise doubts about whether CBDCs can realistically compete with private solutions in retail payments. At the same time, this literature suggests that central banks may not intend to compete directly with private platforms, but rather to provide a public fallback option.

In advanced economies, scholars emphasize strategic autonomy and geopolitical considerations. Demertzis and Martins (2023) argue that the digital euro is motivated not only by technological change, but also by Europe’s dependence on non-European payment providers. Similarly, legal scholarship on China’s e-CNY highlights its role in strengthening state oversight of digital finance and curbing the market power of large private platforms (Laband, 2022).

Despite this growing body of research, a clear analytical gap remains. Much of the literature treats CBDCs either as neutral technological responses to digitalization or as inevitable policy innovations, without explicitly addressing whether they function primarily as public alternatives to the token economy or as defensive mechanisms designed to contain its risks. This paper addresses this gap by framing CBDCs within an explicit alternative-versus-defense framework.

3. Argument: Promise and Risk of CBDCs

CBDCs offer significant potential benefits that align with some of the promises of the token economy. As digital instruments issued by central banks, CBDCs can support faster and cheaper payments, enhance financial inclusion, and enable programmable features for targeted fiscal or financial applications (IMF, 2023). In wholesale contexts, CBDCs may facilitate the settlement of tokenized assets and improve efficiency in capital markets.

At the same time, CBDCs carry substantial risks. Poorly designed CBDCs could disrupt the banking system by encouraging deposit migration from commercial banks to central banks. Concerns over privacy, surveillance, and data governance may undermine public trust if safeguards are insufficient. Moreover, if CBDCs fail to offer a compelling value proposition relative to private digital payments, adoption may remain limited, as seen in several early launches (Sun & Rizaldy, 2023).

This duality highlights the core tension underlying CBDC initiatives. While CBDCs borrow selectively from the token economy, central banks have deliberately avoided fully decentralized or permissionless designs. Instead, CBDCs represent a cautious modernization of public money, prioritizing stability and control over radical innovation.

4. Case Study: Early CBDC Launches and Pilot Programs

Evidence from early CBDC implementations illustrates the defensive nature of most initiatives. The Bahamas, Nigeria, and Jamaica launched retail CBDCs with objectives centered on financial inclusion and payment resilience. However, adoption has been slow, particularly where private digital payment alternatives were already widely available (Sun & Rizaldy, 2023). These cases suggest that CBDCs are not being driven primarily by consumer demand but by policy objectives.

In larger economies, the defensive rationale is even more pronounced. China’s e-CNY pilot is closely linked to efforts to regulate dominant private payment platforms and strengthen state oversight of digital finance (Laband, 2022). The project emphasizes control, compliance, and competition rather than decentralization. In Brazil, the Drex initiative builds on the success of Pix and focuses on wholesale settlement and tokenized assets under central bank supervision, reflecting a cautious integration of tokenization rather than an endorsement of private digital money (Gomes, 2025).

Similarly, the European Central Bank’s digital euro project prioritizes strategic autonomy and the preservation of public money in an increasingly digital payments landscape dominated by non-European providers (Demertzis & Martins, 2023). Together, these cases support the interpretation of CBDCs as primarily defensive responses.

5. Policy Implications

The analysis suggests several important policy implications for governments and central banks. First, CBDC design should clearly prioritize public policy objectives such as monetary sovereignty, financial stability, and trust, rather than attempting to replicate private token-based systems, which may introduce fragmentation and systemic risk (Bank for International Settlements [BIS], 2020; Demertzis & Martins, 2023). Second, governments should invest in robust legal and institutional frameworks that ensure privacy protection, sound data governance, and interoperability with existing financial infrastructures, as these elements are essential for public trust and effective adoption (International Monetary Fund [IMF], 2023).

Third, policymakers should recognize that CBDCs alone are unlikely to drive financial inclusion or innovation without complementary reforms, including digital literacy initiatives, competition policy, and appropriate incentives for private intermediaries to participate in the ecosystem (Sun et al., 2023). Finally, international coordination among central banks and regulators is essential to prevent regulatory fragmentation and to ensure that CBDCs enhance, rather than undermine, the stability and efficiency of the global monetary system (BIS, 2020; IMF, 2023).

6. Conclusion

This paper examined whether central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) function primarily as public alternatives to the token economy or as defensive reactions by central banks. The evidence indicates that CBDCs represent a hybrid, but predominantly defensive, policy response. While they selectively incorporate features associated with token-based systems, their core purpose is to preserve the relevance of public money, maintain monetary sovereignty, and safeguard financial stability in an increasingly digital financial environment (Bank for International Settlements [BIS], 2020; International Monetary Fund [IMF], 2023; Demertzis & Martins, 2023).

As private digital finance continues to evolve, central banks face a critical strategic choice: remain passive observers of monetary innovation or actively modernize public money under sovereign governance. CBDCs represent an important step in this modernization process; however, their long-term success will depend on careful design, clearly articulated policy objectives, and sustained public trust, rather than technological novelty alone (IMF, 2023; Sun et al., 2023).

References

Atlantic Council. (2024). Central bank digital currency tracker. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/cbdctracker/

Bank for International Settlements. (2020). Central bank digital currencies: Foundational principles and core features. https://www.bis.org/publ/othp33.pdf

Demertzis, M., & Martins, C. (2023). Progress with the digital euro. Intereconomics, 58(4), 195–200. https://doi.org/10.2478/ie-2023-0041

Gomes, R. D. B. (2025, May 20). Emerging technologies, lessons from Pix and Drex, and future perspectives [Speech]. Digital Money Summit 2025, London, United Kingdom.

International Monetary Fund. (2023). IMF approach to central bank digital currency capacity development. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Policy-Papers

Laband, J. (2022). Existential threat or digital yawn: Evaluating China’s central bank digital currency. Harvard International Law Journal, 63(2), 515–575. https://harvardilj.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/Laband.pdf

Nakamoto, S. (2008). Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system [White paper]. Bitcoin.org. https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf Sun, T., Tsuda, N., Murphy, K., & Rizaldy, R. (2023). Some lessons from Asian e-money schemes for the adoption of central bank digital currency (IMF Working Paper No. 23/123). International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2023/06/Some-Lessons-from-Asian-E-Money-Schemes-for-the-Adoption-of-Central-Bank-Digital-Currency-534040