The Comprehensive Guide to Corporate Cash Flow: From Operating Cash Flow to Free Cash Flow

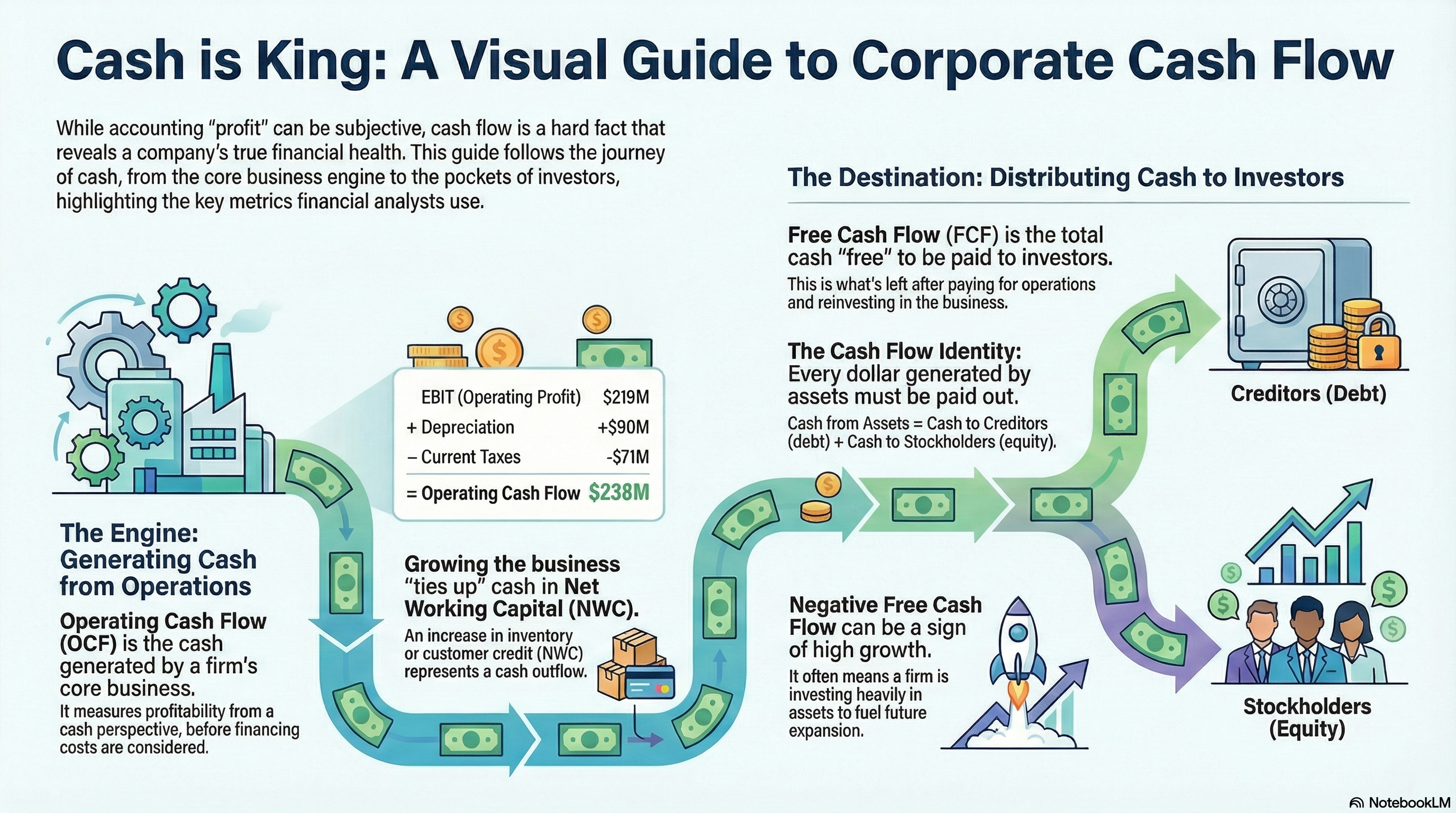

In the world of accounting, “Profit” is an opinion, but “Cash” is a fact. While many investors focus on Net Income, seasoned financial analysts know that the true value of a firm lies in its ability to generate cash flow.

In this exhaustive guide, we will break down the mechanics of the Cash Flow of the Firm, explain the critical role of Net Working Capital (NWC), and demonstrate how to reconcile the cash flows generated by assets with the cash flows paid to investors.

Podcast format

Part 1: Net Working Capital (NWC) – The Firm’s Lifeblood

Before we can calculate cash flow, we must understand the “buffer” of the business: Net Working Capital.

What is Net Working Capital?

Net Working Capital represents the short-term liquidity of a firm. It is the difference between what a company owns in the short term (Current Assets) and what it owes in the short term (Current Liabilities).

- Current Assets: Cash, inventory, and accounts receivable (money owed by customers).

- Current Liabilities: Accounts payable (money owed to suppliers) and short-term debt.

The Formula:

NWC = Current Assets – Current Liabilities

The Importance of “Change in NWC”

In finance, we don’t just care about the total NWC; we care about the Change in NWC. When a firm grows, it usually buys more inventory and allows more customers to buy on credit. This “ties up” cash.

- A Positive Change in NWC is an outflow of cash (the firm spent cash to increase its short-term assets).

- A Negative Change in NWC is an inflow of cash (the firm reduced its investment in current assets).

Part 2: Operating Cash Flow (OCF) – Measuring Core Performance

Operating Cash Flow is the cash generated by the firm’s day-to-day business activities. It tells us whether a company’s primary products or services are actually profitable from a cash perspective, before considering how those operations are financed.

The OCF Calculation (Finance Perspective)

To calculate OCF, we start with Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT), add back depreciation (because it’s a non-cash expense), and subtract current taxes.

| Line Item | Explanation | Example |

| EBIT | Operating profit before interest/taxes | $219M |

| + Depreciation | Non-cash accounting write-off | +$90M |

| – Current Taxes | Actual tax cash outflow | -$71M |

| = Operating Cash Flow | The cash “engine” output | $238M |

Note: In finance, we do not subtract interest when calculating OCF because interest is a financing expense, not an operating one.

Part 3: The Statement of Cash Flows (Accounting vs. Finance)

While the Finance perspective focuses on “Total Distributable Cash Flow,” accountants use the Official Statement of Cash Flows. This statement is divided into three distinct sections:

1. Cash Flow from Operating Activities

This begins with Net Income and “adjusts” it. It adds back depreciation and deferred taxes and accounts for changes in current assets and liabilities. For example:

- Increase in Inventory: Subtract (Uses cash).

- Increase in Accounts Payable: Add (Saves cash).

2. Cash Flow from Investing Activities

This reflects the firm’s investment in long-term health. It includes:

- Acquisition of Fixed Assets: (Capital Spending/Outflow).

- Sale of Fixed Assets: (Inflow).

3. Cash Flow from Financing Activities

This tracks the movement of money between the firm and its owners/creditors:

- Retirement of Debt: (Outflow).

- Proceeds from New Stock Issue: (Inflow).

- Dividends Paid: (Outflow).

Part 4: The Cash Flow Identity – The Golden Rule of Finance

One of the most powerful concepts in corporate finance is the Cash Flow Identity. It states that the cash flow from the firm’s assets (CF(A)) must equal the cash flow to the firm’s creditors (CF(B)) and stockholders (CF(S)).

CF(A) = CF(B) + CF(S)

Cash Flow to Creditors (Bondholders)

Creditors are paid “Debt Service.” This is the interest paid plus any repayment of principal, minus any new borrowing.

- Formula: Interest Paid – Net New Borrowing = CF(B)

Cash Flow to Stockholders (Equity Investors)

Stockholders receive cash through dividends and stock repurchases, but this is offset by any new equity the company raises by selling stock.

- Formula: Dividends Paid – Net New Equity Raised = CF(S)

Part 5: Free Cash Flow (Total Distributable Cash Flow)

The term Free Cash Flow (FCF)—also called “Total Distributable Cash Flow”—is arguably the most important metric for stock valuation. It is the cash that is “free” to be distributed to investors because it isn’t needed for:

- Operating Expenses (already covered by OCF).

- Capital Spending (buying new equipment/buildings).

- Net Working Capital (stocking the shelves).

Why FCF Can Be Negative

It is common for rapidly growing firms to have negative Free Cash Flow. This isn’t necessarily a bad sign—it often means the firm is investing heavily in fixed assets and inventory to support future growth that will eventually lead to massive positive cash flows.

Summary: Key Takeaways for Success

- Cash Flow ≠ Net Income: Net income includes non-cash items and ignores capital spending.

- NWC is a Usage of Cash: Growing firms must “spend” cash to maintain higher levels of inventory and receivables.

- The Identity Must Balance: Every dollar generated by assets must either be kept in the business or paid out to those who provided the capital (debt and equity).