Introduction

Technological change is accelerating at an unprecedented pace, disrupting industries and demanding that businesses adapt or risk obsolescence. In today’s era of digital transformation, often dubbed the Fourth Industrial Revolution, companies face constant pressure to innovate and embrace new technologies (weforum.org). This article examines how organizations navigate such transitions and the consequences when they fail to do so. We explore case studies of once-dominant companies – Kodak, BlackBerry, Nokia, Blockbuster, and Yahoo – that struggled with major technological shifts. Through these examples, we analyze key factors like SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis, communication, and leadership in business innovation. The goal is to draw lessons on effective change management and underscore the importance of adapting to rapid technological change in the digital age.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution: Challenges and Opportunities

The Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) refers to the current wave of technological innovation – a fusion of advances in artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), Big Data analytics, robotics, and more – that is blurring the lines between the physical, digital, and biological spheres (weforum.org). What makes this revolution distinct is the exponential velocity and global scope of change. As noted by the World Economic Forum, 4IR technologies are “disrupting almost every industry in every country” with unprecedented speed (weforum.org). From manufacturing to healthcare, businesses are leveraging connected devices and AI-driven insights to reinvent processes and products. For example, IoT sensors combined with AI enable predictive maintenance in factories, allowing companies to detect equipment issues and schedule fixes before breakdowns occur (eetimes.com). Such data-driven innovations can dramatically increase efficiency and reduce costs.

The opportunities presented by 4IR are immense. Companies that harness emerging technologies can unlock new levels of productivity, develop smarter products and services, and access markets that were previously out of reach. Early adopters of digital platforms and analytics have seen improvements in supply-chain effectiveness and customer personalization, leading to competitive advantage (weforum.org). However, these advancements also come with significant challenges. Industries are experiencing upheaval as automation and digital business models displace traditional ones. There is a real risk of workforce disruption – as repetitive tasks become automated, some jobs disappear even as new high-skill roles are created (weforum.org). Moreover, organizations face a growing digital divide: those slow to change may fall far behind agile innovators. The 4IR has been linked to widening economic inequality, since the benefits of innovation often accrue to those with the skills and capital to exploit new technologies (weforum.org).

For business leaders, the Fourth Industrial Revolution demands proactive adaptation. It is not just about adopting new tech tools, but about rethinking business models and strategies for a digital world. Companies must invest in learning and development to equip their workforce with new skills, and they must be willing to experiment and innovate continually. The following case studies of major firms illustrate what can happen when a company fails to effectively navigate a technological transition – and underscore why agility and strategic foresight are now core to survival.

Case Study: Kodak – Missing the Digital Photography Revolution

Founded in 1888, Kodak was an icon of the photography industry throughout the 20th century. By the 1970s, Kodak commanded a dominant position in film and camera sales (36-hr.com). Ironically, Kodak itself invented the first digital camera in 1975 – a groundbreaking innovation by engineer Steven Sasson – but the company’s management feared it would cannibalize their film business and shelved the project (36-hr.com). As digital photography technology matured in the 1990s and 2000s, competitors seized the opportunity that Kodak had identified but ignored. Kodak’s leadership, entrenched in a fixed mindset and committed to its profitable film sales, continued to dismiss digital imaging as a serious threat or opportunity for too long (36-hr.com). The company was initially “blind to other strategies” beyond its razor-and-blades film business and simply ignored the call of the digital age when the time was ripe to transition (36-hr.com).

By the early 2000s, consumer preferences had clearly shifted to digital cameras and, later, smartphone photography – yet Kodak was lagging in digital product offerings. The consequence of this hesitation was dire. Kodak’s once-formidable strengths (brand reputation, worldwide distribution, expertise in film chemistry) became weaknesses when new technology changed the rules of the game. In 2012, Kodak filed for bankruptcy, cementing its status as a classic example of a company that failed to adapt to a disruptive innovation (36-hr.com). As one analysis put it, Kodak is “often cited as an iconic example of a company that failed to grasp the significance of a technological transition” that threatened its core business (36-hr.com). The most valuable lesson from Kodak’s decline is that even a company celebrated for innovation can falter if it doesn’t push aggressively into uncomfortable new territory. Kodak had the technical insight – it built the first digital camera – but lacked the strategic courage and vision to embrace change. In hindsight, Kodak’s leadership admitted that they missed the moment; as one commentary lamented, despite being an industry pioneer, “Kodak simply disregarded the new digital technology’s implications” until it was too late (36-hr.com). This case highlights how technological change can swiftly turn a market leader into a cautionary tale. Kodak’s downfall underscores the importance of continually aligning corporate strategy with emerging technological realities, lest today’s strength become tomorrow’s obsolete legacy.

Case Study: BlackBerry – Falling Behind in the Smartphone Era

Once synonymous with smartphones, BlackBerry (Research In Motion) offers another example of a dominant company toppled by technological transition. In the mid-2000s, BlackBerry devices – with their signature physical keyboards and secure email – were ubiquitous in enterprises and governments. As late as 2011, BlackBerry still held over a 30% share of the smartphone market in key regions (for instance, 33% in the UK in December 2011) (inspireip.com). However, the launch of Apple’s iPhone in 2007 and the rise of Google’s Android platform marked a paradigm shift toward full-touchscreen devices with rich app ecosystems. BlackBerry’s leadership underestimated how rapidly consumer preferences were evolving. The company was initially “content to serve” its niche of corporate power-users and clung to its existing strengths – physical keyboards, strong security, and proprietary messaging (BBM) – while failing to recognize that mainstream consumers craved larger touch screens and a vast selection of apps (inspireip.com). BlackBerry did attempt to respond (e.g. with the BlackBerry Storm in 2008, its first touchscreen phone), but the product was rushed and flawed – the Storm suffered from software bugs and a lack of popular apps, and reportedly had a “100% return rate” from dissatisfied customers (inspireip.com). Co-CEO Jim Balsillie later acknowledged that the botched Storm launch was “disastrous” and that it was the moment he realized BlackBerry “couldn’t compete” head-to-head with Apple’s iPhone on high-end hardware (inspireip.com).

In the following years, BlackBerry’s market share collapsed as iPhone and Android handsets surged. BlackBerry’s focus on its existing enterprise customer base led it to miss out on billions of potential consumer customers, and it made strategic missteps such as limiting its popular BBM messaging service to BlackBerry devices (allowing cross-platform apps like WhatsApp to capture the wider market) (inspireip.com). By 2016, BlackBerry’s share of the global smartphone market had effectively dropped to 0%, and the company announced it would stop producing smartphones altogether (inspireip.com). Its final phone model, the BlackBerry Priv running Android, launched in 2015 as a last attempt, but it was far too late to regain relevance (inspireip.com). BlackBerry transitioned to a software and services company in the aftermath, but the hardware business that made it famous was gone. The downfall of BlackBerry illustrates how innovation inertia and a false sense of security in a once-dominant market position can be fatal. The company’s leaders were late to recognize touchscreen smartphones as a strategic threat and an opportunity to reinvent their product line. In short, BlackBerry failed to adapt to technological change, providing a cautionary tale that past success is no guarantee of future survival in the fast-moving tech industry (predictableprofits.com).

Case Study: Nokia – The Demise of a Mobile Leader

Nokia was the world’s largest mobile phone manufacturer in the late 1990s and early 2000s, a Finnish powerhouse that seemed unstoppable. Even in 2007, when Apple introduced the iPhone, Nokia still retained a roughly 50% share of the global cell phone market and was posting record profits (predictableprofits.com). Yet within a few short years, Nokia’s fortunes took a dramatic turn. By 2013, Nokia had lost around 90% of its market value compared to its peak, and its handset division was sold off after failing to keep up with the smartphone revolution (predictableprofits.com). The collapse of such a dominant player reveals several critical mistakes in navigating technological transition. Nokia’s leadership was famously described as complacent – or “cocky” – and the organization’s culture became slow-moving and inflexible (predictableprofits.com). Internally, Nokia continued to rely on its aging Symbian operating system and traditional handset designs well after it was clear that consumers preferred the new paradigms introduced by iOS and Android. In an attempt to catch up, Nokia partnered with Microsoft in 2011 to use Windows Phone software, but this move was a belated gamble that never gained traction in a market already dominated by Apple and Android devices.

Several analyses of Nokia’s failure highlight a “lack of vision” at the top and dysfunctional organizational structures that prevented rapid innovation (predictableprofits.com). Engineers at Nokia reportedly saw the promise of touchscreen smartphones and app-centric ecosystems, but management underestimated their importance and feared moving away from Nokia’s feature-phone stronghold. As a result, Nokia ignored or dismissed many early warning signs of the changing consumer expectations (predictableprofits.com). The company also misjudged the software aspect of the smartphone race – while Nokia’s hardware was world-class, its software/UI experience lagged behind rivals. This misalignment became an insurmountable weakness. A poignant (though perhaps apocryphal) quote attributed to a Nokia CEO during the company’s final press conference was, “We didn’t do anything wrong, but somehow, we lost.” Whether or not those exact words were said, the sentiment captures Nokia’s predicament: executing the old playbook well was not enough when the rules of the game had changed. The Nokia case teaches that continuous innovation and willingness to radically change course are necessary in the face of disruptive technology. No market leader, however invincible it may seem, is infallible – as Nokia’s rapid fall from dominance clearly demonstrates (predictableprofits.com).

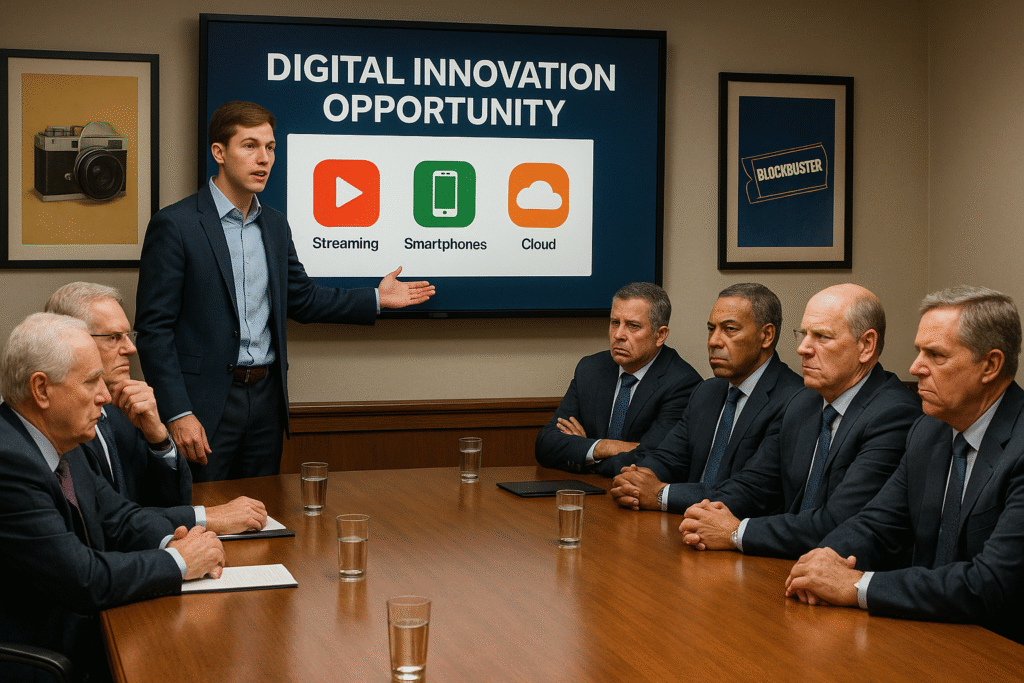

Case Study: Blockbuster – Failing to Respond to Digital Disruption

Blockbuster, the video rental giant of the 1990s and early 2000s, is often cited as the poster child for a business undone by digital disruption. At its peak, Blockbuster operated over 5,000 stores (with some 84,000 employees in 2004) and was a ubiquitous presence in American life for movie and game rentals (v500.com). The company, however, did not foresee the rapid shift in how consumers would access media. As broadband internet expanded and DVDs gave way to on-demand streaming, Blockbuster remained fixated on its brick-and-mortar model. The company was painfully slow to offer online rentals or streaming options, even as upstart competitor Netflix began mailing DVDs and later launched a streaming service in 2007 (v500.com). Blockbuster’s leadership viewed Netflix’s model initially as a niche market or a trivial inconvenience, rather than an existential threat. In one of the most infamous missed opportunities in business history, Blockbuster’s executives literally laughed at a 2000 offer from Netflix’s founders to sell Netflix to Blockbuster for just $50 million (factr.me). Blockbuster rebuffed the offer, failing to grasp that Netflix was laying the groundwork for a new digital-first model of entertainment distributionfactr.me.

By the time Blockbuster recognized the importance of online streaming – finally launching its own streaming service in 2010 – Netflix had already become a household name and captured a huge lead in subscribers and technology. Blockbuster’s late pivot was “too little, too late” (factr.me). The company, burdened by thousands of retail outlets and associated costs, could not effectively compete with the agile, internet-based model of Netflix. Moreover, Blockbuster was saddled with debt from years of expansion and had a corporate culture averse to drastic change. All these factors left it ill-prepared to reinvent itself when the industry shifted under its feet (factr.mefactr.me). Ultimately, Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy in 2010, its market value and customer base decimated (v500.com). Analysts have noted that Blockbuster “failed because it couldn’t—and wouldn’t—evolve.” (factr.me) The company’s demise was not due solely to Netflix’s rise, but rather Blockbuster’s own refusal to embrace new technology and business models in a timely manner (v500.com). Blockbuster had ample resources and a strong brand – advantages that could have been leveraged to lead the digital transition – but what it lacked was vision. Former Blockbuster CEO John Antioco reflected on the downfall, admitting, “We had the resources, we had the brand. What we didn’t have was the vision.” (factr.me). The Blockbuster story vividly illustrates that in the face of digital transformation, standing still is the fastest way to go extinct. Companies must be willing to disrupt their own successful models before competitors do it for them. In short, digital transformation isn’t optional – as one analysis succinctly put it, businesses that ignore disruptive change “often disappear” (factr.me).

Case Study: Yahoo – Lessons from a Fallen Internet Giant

In the early days of the internet, Yahoo was a pioneer and titan of the web. By 2000, during the dot-com boom, Yahoo’s diversified online services (web directory, email, news, social media, photo sharing and more) made it the world’s most visited web portal and a company valued at around $125 billion (medium.com). However, over the ensuing years, Yahoo became a prime example of squandered opportunities and strategic missteps during technological transition. As faster search engines, social networks, and targeted advertising platforms emerged, Yahoo struggled to focus on a clear core business. Perhaps the most glaring missed opportunity was Yahoo’s failure to capitalize on search. In 1998, Yahoo had the chance to buy Google (then a fledgling search engine) for a mere $1 million, but declined (chatrisityodtong.com). A few years later, in 2002, Yahoo realized Google’s potential and attempted to acquire it for $3 billion, only to walk away when Google’s founders insisted on $5 billion (chatrisityodtong.com). The opportunity slipped away, and Google skyrocketed, eventually eclipsing Yahoo in search and online advertising. Similarly, Yahoo missed the rise of social media and user-generated content – despite owning early blogging and photo-sharing platforms (like Tumblr and Flickr), Yahoo failed to innovate around them, ceding leadership to newcomers like Facebook.

Strategic indecision and frequent leadership changes at Yahoo compounded the problem. The company jumped between initiatives – from original media content, to tech platforms, to acquisitions – without ever developing a dominant position in any post-portal arena. In 2008, Microsoft offered to buy Yahoo for approximately $44 billion, an offer Yahoo’s leadership refused in hopes of negotiating a higher price or pursuing their own turnaround (chatrisityodtong.com). This decision proved catastrophic: by 2016, Yahoo’s core business was sold to Verizon for just $4.8 billion (chatrisityodtong.com), a tiny fraction of its former value. In the span of about a decade, Yahoo went from industry leader to an almost cautionary footnote. The fall of Yahoo underscores several lessons: having a broad suite of services is not enough if you lack a coherent strategy; recognizing and acting on key technology trends (like search algorithms, social networking, and mobile apps) is essential; and even enormous early success can evaporate if a company becomes complacent or unfocused. Yahoo’s story is ultimately one of missed opportunities. As one commentary summarized, Yahoo “missed out on hundreds of billions” by failing to acquire or compete effectively with Google and Facebook when it mattered most (chatrisityodtong.com). For today’s businesses, Yahoo’s fate is a reminder that continuous innovation and decisive strategic leadership are critical in fast-changing markets. No amount of past success can substitute for the ability to anticipate and adapt to new technological waves.

SWOT Analysis for Navigating Digital Transformation

In analyzing these cases, it becomes clear that a robust SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) could have been a valuable tool to guide better decision-making during technological transitions. SWOT analysis is a strategic planning method that forces an organization to take a hard look at internal capabilities and external environment before making major changes (eptura.com). Companies often use SWOT when considering a significant shift – for example, pursuing a new digital business model or responding to disruptive technology in the market (eptura.com). By mapping out strengths and weaknesses (internal factors) alongside opportunities and threats (external factors), business leaders can gain a 360-degree view of where the company stands and what challenges or openings lie ahead (eptura.com). Importantly, this process encourages data-driven decision-making rather than relying on assumptions (eptura.com). In the context of digital transformation, a SWOT analysis compels executives to confront the realities of technological change: Are our core products becoming outdated (threat)? Do we have capabilities that could give us an edge in a new paradigm (strength)? What new revenue streams or markets could we tap with emerging tech (opportunity)? Where are we vulnerable to agile competitors (weakness)?

For instance, if Kodak’s management had objectively assessed its situation in the 1990s, they would have listed an obvious threat: the rise of digital photography eroding film sales. They might have also seen an opportunity: Kodak’s own innovation in digital imaging, combined with its brand, could have made it a leader in the new market. Similarly, a SWOT analysis for Blockbuster around 2005 would have highlighted the mounting threat of broadband internet enabling streaming services, as well as Blockbuster’s internal weaknesses like heavy debt and an inflexible store-based cost structure. On the flip side, Blockbuster’s brand loyalty and large customer base were strengths that, if leveraged in time (for example, to launch a streaming platform early), could have been turned into opportunities in the digital realm. The failing companies we discussed often overlooked external threats or overestimated the durability of their strengths. A candid SWOT exercise might have challenged those rosy assumptions. It also could have encouraged these firms to be more proactive – identifying emerging technologies as opportunities to invest in, rather than perceiving them only as threats once competitors capitalized on them.

Beyond crisis response, performing regular SWOT analyses helps firms stay vigilant. In fast-moving industries, it’s wise to periodically reevaluate: what new tech trends are on the horizon that could alter our business? Do we have hidden strengths (like R&D capabilities or data assets) that we can apply to innovate? Are there partnerships or acquisitions (opportunities) that could position us for the future? By integrating SWOT analysis into the strategic planning cycle, organizations can better anticipate change and craft strategies that play to their strengths while addressing weaknesses. In sum, SWOT analysis is a straightforward yet powerful tool for navigating technological change. It pushes leaders to align their company’s internal reality with external realities – a step that companies like Nokia and Yahoo, in retrospect, did not fully take. Going forward, businesses should use SWOT-driven insights to inform their approach to digital transformation, ensuring they are neither blindsided by threats nor late to seize new opportunities.

Communication Strategies and Change Management

Effective communication is one of the most crucial – and undervalued – elements of successful change management during technological transitions. Research shows that the majority of change initiatives fail to meet their goals, often due to employee resistance or lack of management support (mckinsey.com). Proactive communication strategies can significantly reduce resistance to change by building understanding, trust, and buy-in among stakeholders. When a company is about to undertake a major change (such as adopting a new technology or altering its business model), leadership should communicate early and often about what is happening and why. Uncertainty breeds rumors and fear; providing clear, honest information helps preempt the “void” that people might otherwise fill with worst-case assumptions (betterup.com). In practice, this means leaders should share as much as they know, as soon as they can – even if all the answers aren’t available yet. Admitting “we’re still evaluating options” or “we’ll update you as soon as decisions are made” is better than silence. A transparent approach keeps employees from feeling blindsided and fosters a sense of inclusion in the change process (betterup.combetterup.com).

Equally important is two-way communication. Employees on the front lines often have insights into practical challenges and “blind spots” that management might overlook (betterup.com). Creating channels for feedback – via surveys, town hall meetings, Q&A sessions, etc. – allows leaders to listen to concerns and ideas from staff. This not only helps identify genuine issues that need addressing (for example, a concern about the training timeline for a new system), but also signals to employees that their voices matter in shaping the change (betterup.com). People are more likely to support a transformation if they feel heard and involved.

Moreover, a sound communication plan should educate employees on the value of the change and address the classic question, “What’s in it for me?” (betterup.com). Explaining the rationale – perhaps a new technology will automate mundane tasks, allowing employees to focus on more creative work, or it’s necessary to stay competitive and ensure the company’s longevity – can help skeptics understand the long-term benefits (betterup.com). It’s also wise to acknowledge and validate emotions. Change can be scary; employees may fear job loss or failure in learning new skills. By openly naming those anxieties (e.g., “We know some of you are worried about how this will affect your roles, and that’s understandable”), managers can defuse tension and show empathy (betterup.com). This approach invites a problem-solving dialogue rather than a mutiny of silent resentment.

In practical terms, here are some best practices for communication during technological change:

- Communicate a Clear Vision and Urgency: Articulate why the change is necessary and how it connects to the company’s mission and future. If there is a competitive threat or market opportunity, make that case plainly to all. A sense of urgency (without panic) helps motivate action.

- Build a Guiding Coalition of Change Champions: Identify respected employees or managers who buy into the change and enlist them to help disseminate information and enthusiasm among their peers (betterup.com). When influential colleagues champion the change, others are more likely to get on board.

- Use Multiple Channels and Repeat the Message: Don’t rely on a single email or announcement. Use team meetings, intranet updates, FAQ documents, and one-on-one conversations to ensure everyone hears and understands the message. Reiterate key points over time – what’s obvious to leadership may need reinforcement for others.

- Encourage Feedback and Listen Actively: Provide forums (anonymous if needed) for employees to ask questions and express concerns. Acknowledge their input and respond to it. Even if you can’t accommodate every request, people appreciate knowing they were heard. Listening can also uncover legitimate obstacles to change that management can then address (betterup.com).

- Provide Training and Support: Fear of the unknown is often at the heart of resistance. By offering education, training programs, and resources to help people develop required new skills, you demonstrate an investment in your team’s success. Show employees how the change will make their work easier or more rewarding in the long run (betterup.com).

- Celebrate Quick Wins and Be Honest about Setbacks: As the change progresses, communicate progress and small successes to build confidence. If challenges or delays occur, communicate those too – honesty will maintain credibility. Recognize individuals who embrace the change positively, reinforcing desired behaviors.

By following these communication strategies, leaders can significantly improve the odds of a smooth transition. In our case studies, one can imagine alternate histories where better communication might have helped: for example, if Blockbuster’s top management had clearly communicated the need to build a streaming service years earlier and rallied the organization around that vision, the company might have mobilized in time. Or if Nokia’s leadership had fostered an internal dialogue about the iPhone’s implications in 2007 (rather than dismissing it), they might have unlocked ideas from their engineers to respond faster. In essence, open communication is the glue that holds a change effort together – it aligns the organization, minimizes misinformation, and builds trust. Combined with thoughtful change management (planning, training, stakeholder engagement), strong communication can turn resistance into resolve, helping employees navigate the uncertainties of technological transformation with confidence.

Leadership in the Digital Age

Finally, the role of leadership is perhaps the decisive factor in whether businesses successfully adapt to technological change. In periods of disruption, leaders set the tone and direction for the entire organization. The case studies we explored often boiled down to leadership choices (or mistakes): whether to innovate or stand pat, whether to take risks on new technologies or protect existing products, whether to listen to advisors and trends or to stick stubbornly to a personal conviction. Great leaders in the digital age exhibit a willingness to challenge the status quo and drive change with vision and purpose. A comparative look at leadership styles is instructive. On one hand, a fixed or autocratic leadership style can create an environment that resists new ideas. For example, Kodak’s top executives and board clung to a conservative, film-centric mindset – a culture set by leaders who were unwilling to disrupt a profitable status quo36-hr.com. This “we know best” attitude stifled experimentation and led the company to ignore feedback from forward-thinking engineers and market signals. Similarly, BlackBerry’s leadership became complacent, initially dismissing touch-screen smartphones as a fad and doubling down on what had worked in the past. These leaders were reactive rather than proactive, and by the time they acted, the game was largely over.

In contrast, transformational leadership has proven far more effective in guiding organizations through innovation and uncertainty. Transformational leaders are those who inspire and motivate their employees to achieve vision-driven change, rather than simply managing day-to-day operations (cio.com). They are often characterized by open-mindedness, the ability to communicate a compelling vision of the future, and a focus on empowering teams to be creative. Such leaders act as “change agents” in their businesses – they recognize shifting trends in technology and proactively rally the organization to embrace those shifts (cio.com). They also foster a culture where experimentation is encouraged and failure is treated as a learning opportunity rather than a punishable offense. This is crucial when dealing with emerging technologies, because innovation inherently involves some risk and failure on the path to success.

A transformational leader typically practices a more democratic or collaborative style of leadership. They seek input from diverse groups, encourage cross-functional teams, and often break down hierarchies that impede information flow. They focus on developing their people, delegating authority, and building trust – so that employees feel ownership of the change process. For example, such a leader might form an internal innovation task force and empower younger tech-savvy employees to drive a digital project, rather than keeping all decisions at the top. According to CIO.com, transformational leadership “aims to encourage, inspire, and motivate employees to innovate and create the change necessary to shape the future success of the company.” (cio.com) In practice, this style has been vital in the fast-paced tech sector, where leaders need to continuously adapt. Studies have noted that transformational leadership is especially critical in environments of rapid technological innovation, as it cultivates agility and an organizational mindset geared toward growth and adaptation (cio.com).

To compare leadership styles: a transactional leader (focused on routine, short-term performance and maintaining the status quo through rewards/punishments) might excel in stable conditions, but during a technological upheaval, they may falter by prioritizing efficiency over strategic change. On the other hand, a transformational leader looks beyond the immediate quarterly results and invests in long-term capabilities, even if that means short-term disruption. They communicate a sense of urgency about needed changes but also optimism about the future, which can galvanize an organization to move. When Satya Nadella became CEO of Microsoft in 2014, for instance, his transformational approach (emphasizing a “growth mindset,” cloud-first strategy, and breaking silos) is often credited with reinvigorating Microsoft and repositioning it for the cloud computing era – a real-world example of leadership enabling successful tech transition.

Additionally, effective leaders in times of change often exhibit adaptability and continuous learning themselves. They stay informed about technological trends, seek advice from experts, and are willing to pivot strategy when evidence demands it. This personal flexibility at the top encourages a culture where adaptation is valued company-wide. Leadership in the digital age also means knowing when to make bold decisions. There are moments when incremental improvements aren’t enough and a radical shift is required (for example, deciding to discontinue a legacy product in favor of an emerging one). In our cases, leadership hesitancy was costly – Yahoo’s CEOs hesitated to overhaul the company’s cluttered portfolio or invest heavily in search; BlackBerry’s leaders hesitated to abandon their hallmark keyboard design soon enough; Blockbuster’s management hesitated to cannibalize store revenue for streaming revenue. A strong leader must sometimes disrupt their own business before an outside competitor does. This might mean adopting a new technology that renders an old one obsolete, or restructuring a business model, or acquiring a smaller innovator and integrating its approach.

At the same time, leadership in these scenarios is not just about bold moves; it’s also about managing the human side of change (as discussed in the communication section). Leaders need to model the behavior they seek – if adaptation and innovation are desired, the leadership team should be visibly engaged in learning new tools, brainstorming new ideas, and rewarding creativity. They must also build a guiding coalition of other leaders and influencers in the company who are aligned and can help push the change at various levels (kotterinc.com). It’s telling that when companies succeed in transformations, it’s often attributed to leadership. For instance, IBM’s successful shifts in strategy over a century (from hardware to services to AI) are frequently credited to forward-thinking CEOs who anticipated industry changes and acted decisively.

In summary, leadership can make or break a digital transformation. The lessons from failures highlight that a lack of strategic vision, reluctance to embrace change, or inability to rally the organization will likely lead to decline when technology shifts. Conversely, a leadership approach that is visionary, inclusive, and change-oriented can steer even a legacy organization through upheaval to renewed success. As management expert Peter Drucker famously said, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast,” and it is leaders who shape culture. In times of technological transition, leaders must cultivate a culture of agility, innovation, and continuous learning. Those who do so position their companies not just to survive change, but to harness it for competitive advantage.

Conclusion

The experiences of Kodak, BlackBerry, Nokia, Blockbuster, and Yahoo carry a clear message: adaptability is the lifeblood of business survival in the face of technological change. Each of these once-dominant companies was blindsided not simply because technology changed – technology is always evolving – but because they failed to change themselves in time. From these case studies we learn that no amount of market share, brand loyalty, or past success can immunize a company against disruption. The key takeaways are evident. Innovation must be continuous; companies should seek to reinvent rather than rest on their laurels. Deep understanding of one’s internal strengths and weaknesses, as well as external opportunities and threats (through tools like SWOT analysis), is essential to formulating the right strategic response. Open communication and thoughtful change management can turn an organization’s fear into forward momentum, aligning teams around a new vision. And above all, strong leadership in business is crucial – leaders must be courageous and foresighted, willing to steer the company into uncharted waters when the situation calls for it.

Adapting to technological change is not a one-time project but a core competency that businesses need to build for the long term. In the current Fourth Industrial Revolution era, change is exponential and multi-faceted; whether it’s AI, IoT, automation, or some yet unknown innovation, there will always be a “next big thing” around the corner. Companies that cultivate agility, encourage learning, and remain customer-focused are far better positioned to turn disruptions into opportunities. As one observer aptly noted, in both nature and business “it is not the strongest or the smartest that survive, but those who can adapt and evolve most efficiently to change.” (chatrisityodtong.com) In practical terms, this means fostering a culture that is proactive rather than reactive – one that experiments, listens to emerging trends, and isn’t afraid to pivot when the evidence demands.

The importance of adapting to technological change cannot be overstated: it is the difference between thriving and fading away. Businesses that embraced digital transformation (for example, Netflix in streaming, Amazon in cloud computing, or Apple in mobile ecosystems) have reshaped entire industries and achieved remarkable success. Those that did not, we’ve seen, became cautionary tales studied in hindsight. In conclusion, the central lesson for organizations and leaders is to stay curious, stay vigilant, and stay flexible. Technological innovation will continue to accelerate, bringing both upheaval and opportunity. By nurturing a mindset of agility and a strategy of continuous adaptation, businesses can not only survive these transitions but emerge stronger. In a world of rapid technological transitions, change is inevitable – but failure to change is not. The companies that recognize this and act decisively are the ones that will lead in the digital era, turning the challenges of innovation into catalysts for future growth and success.

Sources:

- Schwab, K. (2016). The Fourth Industrial Revolution: what it means and how to respond. World Economic Forum weforum.org.

- 36-HR Training & Consultancy. (2020). How a Fixed Mindset Culture Killed Kodak – The King of Film. (Kodak case study analysis) 36-hr.com.

- InspireIP. (2023). Causes of BlackBerry’s Downfall: A Cautionary Tale. InspireIP Blog inspireip.com.

- Predictable Profits. (2022). Where Did Nokia Go Wrong? Lessons from Their Fall. PredictableProfits.com predictableprofits.com.

- v500 Systems. (2021). Blockbuster vs Netflix – Case Study. v500.com v500.com.

- Factr. (2023). Blockbuster’s Collapse: What Happens When Businesses Ignore Digital Transformation. Factr Blog factr.me.

- Sityodtong, C. (2016). Lessons From Yahoo’s Fall: $125b to $5b. chatrisityodtong.com chatrisityodtong.com.

- Eptura. (2024). SWOT analysis: Finding your way to the digitally connected workplace. Eptura Blog eptura.com.

- McKinsey & Co. (2015). Changing Change Management. McKinsey Insightsmckinsey.com.

- BetterUp. (2022). Overcoming Resistance to Change within Your Organization. BetterUp Blog betterup.com.

- CIO.com. (2024). What is Transformational Leadership? A Model for Motivating Innovation. CIO Magazine cio.com.

- Kotter Inc. (2021). The 8-Step Process for Leading Change. Kotter.com kotterinc.com.