Navigating the Next Wave: Key Signals from Early CBDC Launches and Pilots

Abstract

Since 2020, a small group of jurisdictions have launched central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) for individuals, while major economies have begun crucial pilot phases. This paper analyzes the implementation experience of the first user countries: the Bahamas, Nigeria, and Jamaica, as well as emerging data from the “new wave” of pilot projects in India, China, and Brazil. The central research question concerns the outcomes of these early implementations and how these outcomes inform the trade-offs between financial inclusion, privacy protection, and system resilience. Drawing on capacity-building frameworks from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and recent central bank reports, this study demonstrates that CBDC outcomes depend less on the underlying ledger than on the policies, design choices, and governance of the ecosystem. The results suggest that, while initial adoption follows a slow S-shaped trajectory, the new wave of CBDCs is moving towards programmable use cases and wholesale settlement to differentiate itself from efficient instant payment systems. The article concludes with policy recommendations regarding privacy protection technologies, incentives for intermediaries, and the need for offline capabilities.

Podcast:

1. Introduction

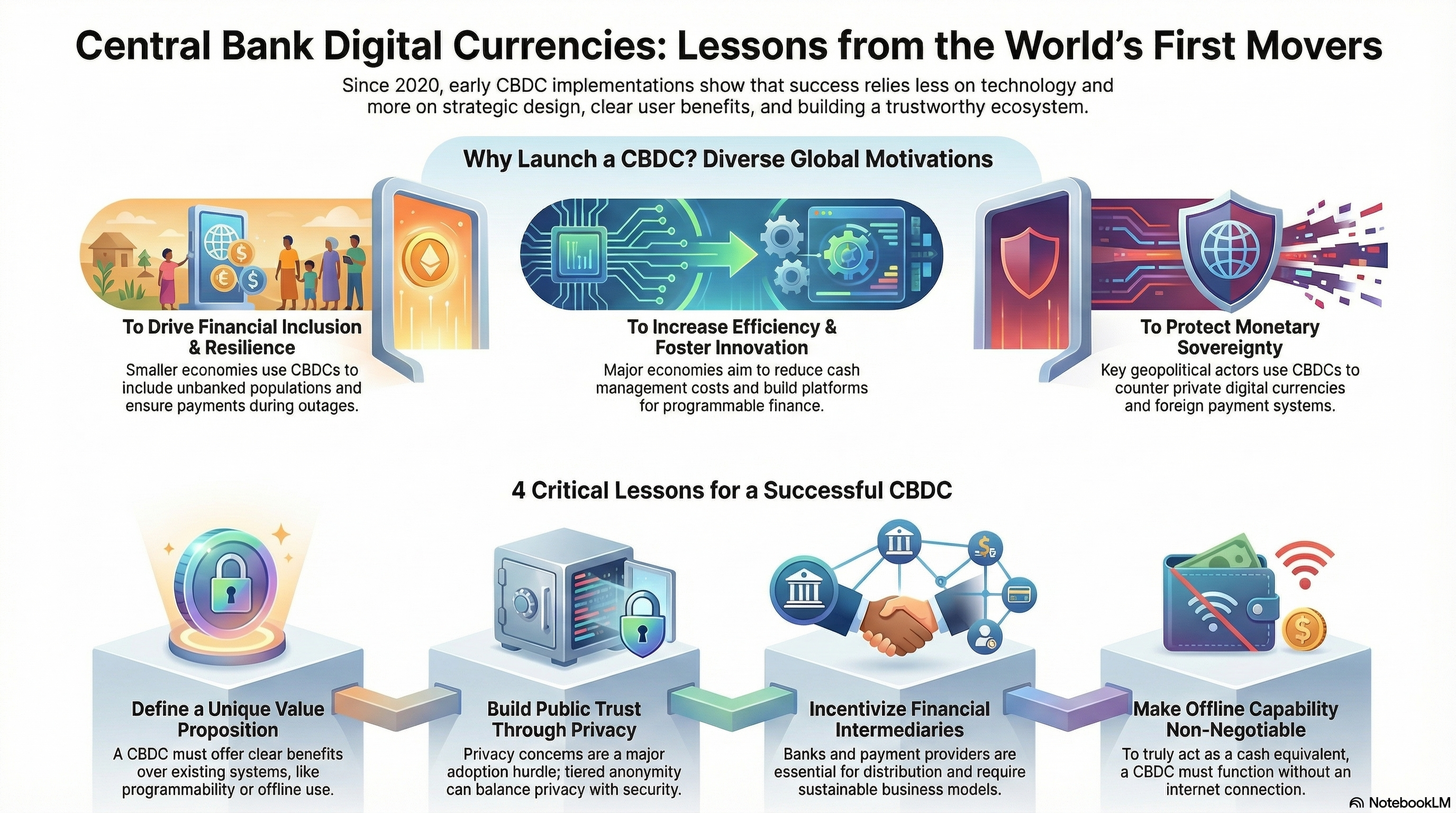

The global payments landscape is undergoing profound transformation, characterized by the decline in cash usage, the rise of private digital assets, and the digitization of finance. In response, central banks have accelerated their research into central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). According to recent assessments, retail CBDC issuance is under consideration in over 100 countries, with most central banks engaging in this area to enhance payments resilience and monetary sovereignty (Sun, Tsuda, Murphy et al., 2023).

Retail central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) represent a publicly accessible sovereign digital currency designed to complement, rather than replace, cash. Since 2020, three jurisdictions have fully launched retail CBDCs: the Bahamas, Nigeria, and Jamaica. Meanwhile, major economies such as India, China, and Brazil have initiated advanced pilot projects that provide crucial data on scalability and use cases. The divergence in motivations is striking: emerging markets often seek to address specific market frictions or promote inclusion, while advanced economies focus on maintaining the relevance of public currency in the digital era (Demertzis & Martins, 2023).

This paper synthesizes the lessons learned from these diverse experiences. It compares the financial inclusion objectives of small economies with the strategic autonomy and efficiency objectives of large economies such as the Eurozone and China. Applying the IMF’s capacity-building framework, the analysis highlights that successful adoption requires a value proposition superior to that of existing electronic money systems (Sun & Rizaldy, 2023).

2. Theoretical Frameworks for Adoption

To understand the trajectory of CBDC implementation, this paper uses two main frameworks derived from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and lessons learned from Asian electronic money systems.

2.1 The “5P” and “REDI” Frameworks

Sun, Tsuda, Murphy, et al. (2023) outline a comprehensive “5P” methodology for CBDC project management: Preparation, Proof of Assumptions, Prototypes, Pilots, and Production. This iterative process allows central banks to validate assumptions regarding technology and user behavior before full-scale issuance. For instance, the “Proof of Assumptions” phase is critical for validating whether specific policy goals, such as financial inclusion, can be met by the proposed technology (Sun, Tsuda, Murphy, et al., 2023).

Complementing this is the concept that adoption is a policy outcome driven by coordinated action. The “REDI” framework: Regulation, Education, Design & Deployment, and Incentives; posits that without clear regulatory guidelines and targeted incentives, adoption stalls regardless of technological readiness (Sun, Tsuda, Murphy, et al., 2023). This framework emphasizes that CBDC is not merely an IT project but a multidimensional policy intervention.

2.2 Lessons from E-Money Schemes

Successful private electronic money systems in Asia, such as Alipay (China) and Paytm (India), offer valuable lessons for the adoption of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). The work of Sun and Rizaldy (2023) indicates that these platforms have thrived by combining different use cases (e.g., ride-hailing, social networks) to create “super-applications” that blend convenience and efficiency. To be competitive, a CBDC must possess four key strengths: trust, convenience, efficiency, and security (Sun and Rizaldy, 2023). Central banks must therefore incentivize payment service providers (PSPs) to develop business models that sustain these strengths within a CBDC ecosystem, as the private sector has already demonstrated that user adoption is facilitated by network effects and ecosystem integration (Sun and Rizaldy, 2023).

3. Drivers of CBDC Issuance

The drivers for CBDC issuance vary significantly by economic context, influencing design choices and implementation strategies.

3.1 Financial Inclusion and Resilience

For island nations and developing economies, the primary motivation is often financial inclusion and physical resilience. In the Bahamas, for example, a key factor has been ensuring continuity of payments across remote islands with uneven connectivity, which has required robust offline functionality (Central Bank of the Bahamas, 2019). Similarly, in Nigeria, the eNaira system was introduced to bridge the digital divide for unbanked populations through tiered KYC (Know Your Customer) requirements that lower barriers to entry, enabling people without formal bank accounts to access the financial system (Central Bank of Nigeria, 2021).

3.2 Operational Efficiency and Innovation

In emerging markets with robust payment infrastructures, the focus is shifting towards efficiency and innovation. The Indian government and the Reserve Bank of India (2022) emphasize that the digital rupee (e₹) aims to reduce the high operational costs of cash management and foster innovation in cross-border payments. Indian authorities clarify that the central bank digital currency (CBDC) is not intended to replace existing digital payment systems like UPI, but rather to offer a sovereign alternative that reduces settlement risk and transaction costs (Reserve Bank of India, 2022).

In Brazil, the Central Bank views the CBDC (Drex) not only as a payment instrument, given the resounding success of its instant payment system, Pix, but also as a platform for programmable finance and the settlement of tokenized assets (Central Bank of Brazil, 2025). The goal is to democratize access to complex financial products by lowering intermediation costs (Duarte, 2024).

3.3 Monetary Sovereignty and Strategic Autonomy

For key geopolitical actors, central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) are a tool of sovereignty. Demertzis and Martins (2023) argue that a digital euro is necessary to preserve the role of public currency as a pillar of the financial system. Furthermore, it is strategically imperative to reduce dependence on non-European payment providers, which currently handle approximately 70% of card transactions in Europe, representing a potential risk to the resilience of payments in the euro area (Demertzis and Martins, 2023).

Laband (2022) notes that the e-CNY is part of a broader strategy to reassert state control over financial flows and data, which had gradually migrated to closed private ecosystems such as Ant Group’s Alipay.

4. Case Studies: The First Movers

4.1 The Bahamas: Sand Dollar

Launched in 2020, the Sand Dollar uses a two-tier distribution model where regulated intermediaries manage services for customers. Its main characteristic is its robust offline operation, essential for an archipelago prone to hurricanes. Although its adoption has been gradual, following an S-curve, the project has demonstrated that offline capability is a prerequisite for the resilience of regions facing connectivity challenges (Sun, Tsuda, Murphy, et al., 2023).

4.2 Nigeria: eNaira

Nigeria’s eNaira (2021) serves as a case study illustrating the challenges of replacing cash with crypto-assets. Despite measures such as interest-free accounts aimed at preventing bank disintermediation, its adoption was initially hesitant. However, the central bank found that integrating the central bank digital currency (CBDC) into government-to-citizen (G2P) social transfer programs provided an essential “seed” for its use, highlighting the crucial role of the state in initiating transactions (Central Bank of Nigeria, 2021).

4.3 Jamaica: JAM-DEX

In Jamaica (2022), the focus was on incentives to encourage adoption. By offering direct sign-up bonuses to early adopters, the central bank successfully accelerated the initial adoption rate. Furthermore, the specific targeting of micro-traders and street vendors, through a simplified registration process, aimed to digitize the informal economy, demonstrating the importance of targeting specific user segments (Bank of Jamaica, 2023).

5. The Next Wave: Pilots in Major Economies

5.1 India: Phased Implementation of e₹

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) (2022) adopted a cautious and phased strategy for the digital rupee, launching separate pilot projects for the wholesale (e₹-W) and retail (e₹-R) segments in late 2022. The wholesale pilot project focuses on settling government securities to reduce transaction costs and settlement risk by anticipating the need for a settlement guarantee infrastructure (Government of India/RBI, 2022). The retail pilot project operates within a limited user group, testing peer-to-peer (P2P) and peer-to-merchant (P2M) transactions via QR codes. The Indian approach emphasizes the importance of learning by doing to avoid disrupting a financial system already undergoing digitization through the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) (Government of India/RBI, 2022).

5.2 Brazil: Drex and the Programmability Pivot

The Brazilian experience offers a crucial turning point in the strategy of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). While Pix already efficiently handles billions of retail transactions, the Central Bank of Brazil (2025) found that a retail CBDC offered only marginal value to consumers. Therefore, the Drex pilot project focuses on a multi-asset programmable DLT platform. Its primary use case is not payments, but the atomic settlement of tokenized assets (such as Treasury bonds) to reduce risks and costs in wholesale markets (Central Bank of Brazil, 2025). This strategy aligns with Duarte’s (2024) observation that Drex’s potential lies in creating new financial products rather than replicating existing ones. The Brazilian pilot project explicitly tests the composability of smart contracts to simplify complex financial transactions (Central Bank of Brazil, 2025).

5.3 China: e-CNY and Managed Anonymity

The Chinese electronic yuan (e-CNY) pilot project is the largest in the world. It is based on a “controlled anonymity” approach: low-value transactions are anonymous, while high-value transactions are traceable to prevent financial crime. Laband (2022) points out that this system aims to reconcile user privacy with state surveillance imperatives, a compromise that seeks to combat financial crime and illegal gambling while preserving the convenience of digital payments. However, this centralized visibility raises significant privacy concerns for Western observers and highlights the state’s desire to maintain control over the money supply (Laband, 2022).

6. Strategic Lessons and Policy Recommendations

6.1 The Privacy Trilemma

Privacy concerns are the main obstacle to the adoption of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) in democratic countries. A study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia (2024) indicates that US consumers are highly skeptical of CBDCs, with the fear of being tracked being a major concern for over 20% of respondents (Akana et al., 2024). The Drex pilot project in Brazil highlighted a “technological trilemma” related to privacy: current solutions (such as zero-knowledge proofs) often degrade the performance (scalability) and programmability of systems (Central Bank of Brazil, 2025). Recommendation: Central banks should invest in privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs) without compromising throughput. A multi-layered privacy protection model (anonymity for low-value transactions, similar to cash payments) is essential to building public trust (Central Bank of Brazil, 2025).

6.2 Defining the Value Proposition

A retail central bank digital currency (CBDC) should not simply replicate existing electronic money. In markets with mature instant payment systems (Brazil, India), the CBDC must offer unique utility, such as programmability (smart contracts) or offline usability. As Sun and Rizaldy (2023) point out, successful adoption depends on targeting clear use cases that connect consumers and merchants, rather than solely on the novelty of the technology. Recommendation: Jurisdictions with efficient retail payment systems should prioritize wholesale CBDCs or programmable platforms to address settlement issues, rather than competing for retail point-of-sale dominance (Duarte, 2024).

6.3 Intermediary Incentives and Ecosystems

Commercial banks and payment service providers (PSPs) are essential to distribution in a two-tier model. However, they risk cannibalizing their own deposit bases and fee income. Sun and Rizaldy (2023) argue that central banks must help PSPs develop sustainable business models, including enabling them to generate value through data-driven services that complement central bank digital currency (CBDC). Recommendation: Central banks should design sustainable business models for intermediaries. This may involve remuneration models where the central bank subsidizes initial infrastructure or allows intermediaries to generate value through value-added services (Sun and Rizaldy, 2023).

6.4 Offline Capability is Non-Negotiable

For a CBDC to truly function as a cash equivalent, it must work without the internet. This was a primary success factor for the Sand Dollar and is a stated requirement for the digital rupee and digital euro. The Government of India/RBI (2022) explicitly states that offline functionality is beneficial for remote locations and offers resilience when mobile networks are unavailable. Recommendation: Developing secure, hardware-based or software-based offline solutions should be a technical priority to ensure resilience and financial inclusion in remote areas (Government of India/RBI, 2022).

7. Conclusion

The experiences of implementing central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) in the Bahamas, Nigeria, and Jamaica offer valuable lessons for major economies currently testing or developing them, such as Brazil, China, and India. These early cases demonstrate that the effectiveness of a CBDC depends less on the sophistication of the technology than on the coherence between design choices, user incentives, and institutional capacity. In these three pioneering countries, adoption remained limited when CBDCs did not offer clear advantages over existing digital payment options or when users and merchants lacked motivation. Nigeria’s experience with the e-Naira illustrates how insufficient value propositions and weak ecosystem incentives can hinder adoption despite strong policy ambitions (IMF, 2023). Jamaica’s JAM-DEX and Eastern Caribbean’s DCash have encountered similar challenges in ensuring sustained adoption, highlighting the importance of public communication, merchant involvement, and progressive readiness assessments.

For the major pilot economies, these experiences highlight several strategic priorities. First, the successful adoption of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) requires an effective two-tiered ecosystem in which intermediaries, banks and non-bank payment service providers, receive clear business and operational incentives to support distribution. Lessons learned from Asian e-money systems show that adoption accelerates when payment service providers can leverage clear regulatory frameworks, scalable business models, and integrated digital platforms (Sun & Rizaldy, 2023). Pilot projects for the electronic yuan (e-CNY) in China demonstrate the benefits of coordinated ecosystem development and strong institutional support (Laband, 2022). Similarly, the Indian digital rupee framework emphasizes coexistence with existing, high-performing systems and the importance of offering new functionalities, such as offline transactions and enhanced security, to justify user migration (Reserve Bank of India, 2022; Ministry of Finance, 2022). Brazil’s Drex initiative adopts a comparable approach, prioritizing financial inclusion through offline functionalities accessible to communities without stable internet access (Duarte, 2024).

Second, these early experiences highlight that public trust is a key factor in the viability of a central bank digital currency (CBDC). A study of US consumers indicates that privacy protection, free access, and offline usability are decisive factors influencing CBDC adoption (Akana et al., 2024). The Bahamas’ Sand Dollar illustrates how privacy-preserving identification tiers can balance AML/CFT requirements with user confidence. For larger economies, establishing trust will require transparent communication, strong cyber-resilience protocols, and clear data-governance frameworks, consistent with the policy guidance developed through the IMF’s CBDC capacity-development program (Sun, Tsuda, Murphy et al., 2023).

Finally, the experiences of early adopters reveal that CBDCs carry meaningful risks if implementation does not adequately account for financial structure, user needs, and payment-system dynamics. These risks include low adoption, disruptions to bank intermediation, operational vulnerabilities, and the potential widening of digital divides if inclusive design is not prioritized (Demertzis & Martins, 2023). This is especially relevant for countries with large rural populations or significant disparities in digital access, such as Brazil and India.

In summary, the emerging evidence suggests that the next phase of CBDCs in large economies will succeed only if policymakers integrate the lessons from early adopters while customizing their approaches to domestic contexts. A viable CBDC for Brazil, China, or India will need to:

(1) deliver distinctive functionalities not currently offered by private payment platforms;

(2) support a balanced two-tier distribution model with sustainable incentives for intermediaries;

(3) incorporate privacy-by-design and robust cyber-security measures; and

(4) align its rollout strategy with national objectives related to financial inclusion, payment resilience, and monetary sovereignty.

By addressing these considerations, the next generation of CBDC projects can avoid the shortcomings observed in smaller economies and evolve into resilient, widely adopted instruments that reinforce the stability and inclusiveness of national payment systems.

References

Akana, T., Cheney, J., & Hunt, R. (2024). Central Bank Digital Currency: Consumer Perspectives in the U.S. (Consumer Finance Institute Special Report). Philadelphia Fed.

Bank of Jamaica. (2023). Annual report 2022: Report and statement of accounts for the year ended 31 December 2022.

Central Bank of Brazil. (2025). Emerging Technologies, Lessons from Pix and Drex, and the Future of Finance [Speech transcript].

Central Bank of Nigeria. (2021). Design paper for the eNaira.

Central Bank of The Bahamas. (2019). Project Sand Dollar: A Bahamas payments system modernisation initiative.

Demertzis, M., & Martins, C. (2023). Progress with the Digital Euro. Intereconomics, 58(4), 195–200.

Duarte, M. (2024). The potential of Drex, the Brazilian CBDC. Conference paper, Hans-Böckler-Stiftung.

Government of India / RBI. (2022). e₹ – India – One of the pioneers in introducing CBDC.

Laband, J. (2022). Evaluating China’s Central Bank Digital Currency. Harvard International Law Journal, 63(2), 515–559.

Philadelphia Fed. (2024). Central Bank Digital Currency: Consumer Perspectives in the U.S. (Consumer Finance Institute Special Report).

Reserve Bank of India. (2022). Concept Note on Central Bank Digital Currency.

Sun, T., & Rizaldy, R. (2023). Some Lessons from Asian E-Money Schemes for the Adoption of Central Bank Digital Currency (IMF Working Paper 2023/123).

Sun, T., Tsuda, N., Murphy, K., et al. (2023). IMF Approach to Central Bank Digital Currency Capacity Development (Policy Paper 2023/016). International Monetary Fund.